Gamification: learning through visual experience in game

One of the possible creative outputs through which visual thinking is made concrete is that of facilitation. However, one of the most common mistakes is to overlap the definition of “gamification” with that of “teambuilding”.

How does facilitation manage to bring together the human, the game and at the same time the visual dimension?

Its territory of application is wide: play meets reality. Reality, play and thought merge on the same playground. But game and play are not the same thing. Any activity can be labeled as play, but the practice of “play” implies finalization: the moment the basis for change is set in motion, a game acquires a purpose.

Playing can be the engine of transformation, and in this sense, the dynamic force of imagination gives extra power to daily practice.

But why specifically through “play”?

Games are part of the activities used by humans to memorize; play can represent a reversal of perspectives from the ordinary. Just as novels make us experience lives we have not lived, games immerse us in forms of reality that we might never have discovered on our own.

Basically, for the development of a functional game, it is sufficient to set goals, bring skills into play, and bring an environment to life. These three elements, in different gradients and in different combinations, can animate any scenario.

One of the most important aspects of successful play is precisely the scenario. We feel safe if we recognize it as explicitly fictional: this fiction is called “organizational metaphor”.

This is a metaphorical framework that uses figurative concepts and images to describe the organization of a company or entity. For example, borrowing our metaphors, the world of superheroes, where employees become an integral part of this reality with their daily actions. Or the world of graffiti art, or any other scenario that can grab our attention and, at the same time, influence corporate culture, leadership and decision-making strategies, as they shape the perception and interpretation of organizational members, regarding to what they do and how they do it.

While under the label of “teambuilding” pass a range of activities with which the visual imagination is relatively associated and the associative value of these practices prevails, rather.

Dropping into a game can be wonderful, intense, and engaging: this is the added strength of communicating through an experience, but the necessary condition for this process to work is the covenant to allow oneself to be drawn in, even before the rules of the game or a purpose are drawn up.

To achieve the desired state of involvement, we let fiction occupy our consciousness for a while, and it is precisely this fact that makes games close to the art form. It is understood, just as in art we seek something that upsets us (something we do not habitually do in real life), so in games we seek what we would normally avoid: failure. Games are united with art through this paradox.

A game more valuable when it gives us the opportunity to fall in safety and envision scenarios that would otherwise be precluded. This concept is very old, just think of primitive humans who gathered in groups for hunting or other activities, deciding to compete just for the sake of it and to keep themselves involved.

“Gamification” is the art of bridling fun and functionally directing it toward real, productive activities. Today, our goal is no longer to hunt for survival or to gather fruit as quickly as possible – although we can learn many other qualities that unite us with any troglodyte – but to hone individual and group skills that optimize our work.

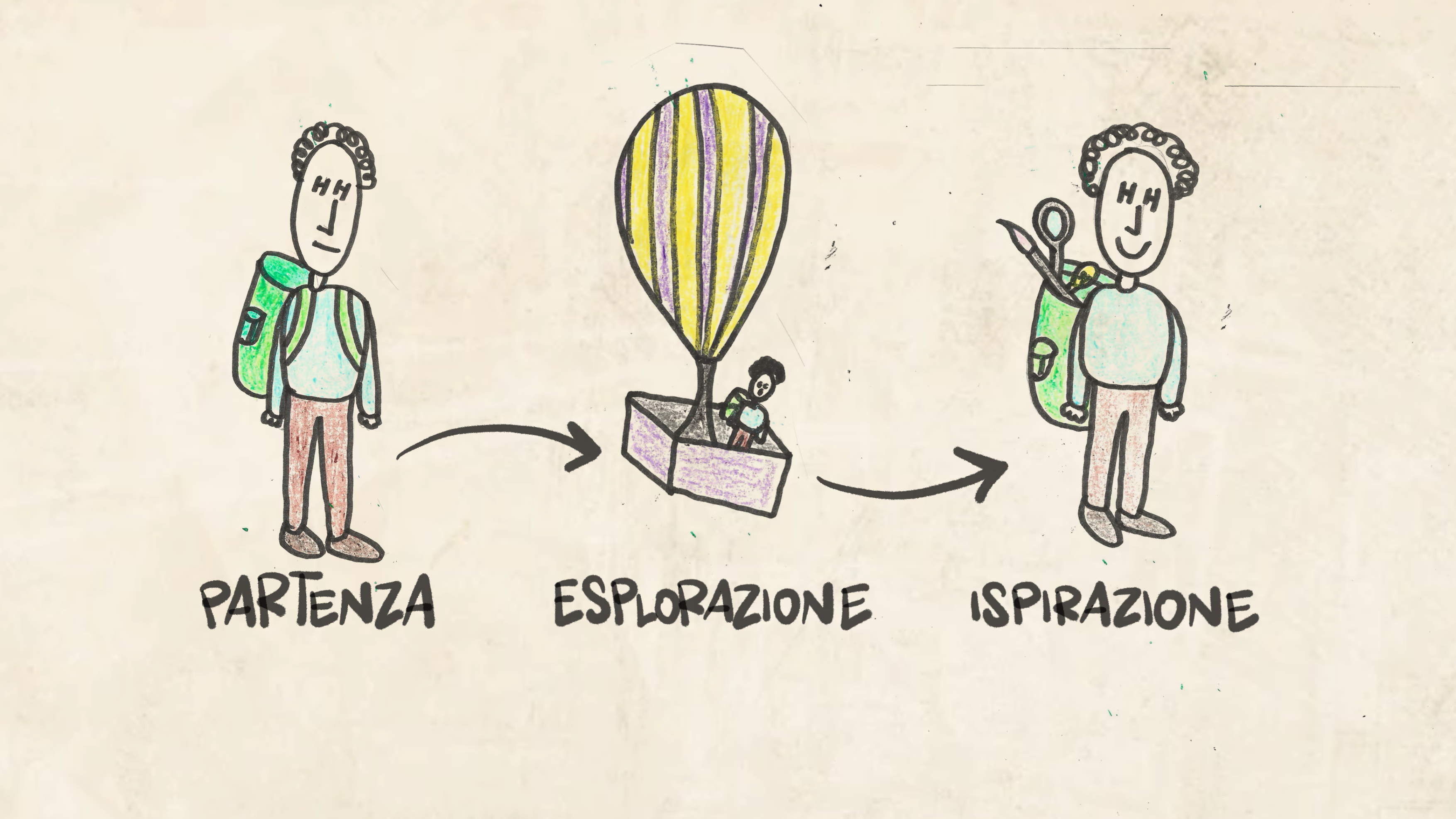

The approach is as simple as it has always been, what changes is how “sophisticated” the goals we want to achieve are. Playing can be a way to take time and still get results through creative thinking. Although the end state in which we arrive may also be uncertain, we need to be clear about where we are starting from.

From a point A we will get to a point B: in between are a series of perhaps even repetitive activities that are meant to keep us engaged. As long as the basic promise of the game is kept, which is to be open to all that this can bring. It is precisely through repetition that a “practice” (as the good Aristotle used to say) is activated: unlike usual practices, a facilitation activity is not meant to achieve a goal quickly. It takes on greater importance the path.

Here we see the skill of the facilitator. The more skillful he/she is in triggering a process of change and identification, in igniting the spark, the fire for the effective mobilization of candidates, the more successful the activity can be said to be and to have effectively laid the groundwork for goal achievement.

If you want to know more:

Y.-K. Chou, Actionable gamification, Milpitas, Octalysis Media, 2019.

S. Fioretti, Il valore educativo del gioco. Gamification e game based learning nei contesti educativi, Milano, FrancoAngeli, 2023.

D. Gray, S. Brown, J. Macanufo, Gamestorming, Palermo, Flaco Edizioni, 2021.

M. Thibault, Gamification urbana. Letture e riscritture ludiche degli spazi cittadini, Ariccia, Aracne, 2016.

C. Thi Nguyen, Giocare è un’arte, Torino, Add Editore, 2020.

©Illustrations by Lionel Cotromino